Eva Schloss, a 96-year-old companion of Jewish war diarist Anne Frank and a survivor of the Nazi death camps, became Anne’s posthumous step-sister in November 1953 after her mother married Otto Frank, Anne’s father.

Eva Geiringer, who was ten years old at the time, lived with her parents and brother in Holland when Germany invaded on May 10, 1940. The Geiringers and other Dutch Jews proceeded to the harbor three days later in an attempt to board a ship that would take them to England. After hours of waiting, they were finally sent home because all the ships had either departed or were full.

In a matter of days, all Dutch Jews were required to identify themselves by wearing a bright yellow Star of David on their clothing. “Never take off your coat if your dress has not got a star on it,” Eva’s mother advised young Eva. The Germans will arrest any Jew who is stopped and does not display the star.

The family fled into hiding with the aid of the Dutch resistance after Eva’s older brother Heinz was summoned to a “work camp” in Germany on July 6, 1942. They separated for protection, with Eva and her mother residing in one safe house and her father and brother in another. Her period in hiding was “full of warmth and love, and terror of being discovered,” she later said.

A startling ring on the doorbell startled the mother and daughter as they celebrated Eva’s 15th birthday in hiding on May 11, 1944. She subsequently remembered, “To our sickening horror, we heard the Gestapo storming in.” They pulled us violently downstairs and out into the street to be marched to the Gestapo headquarters a few streets away while brandishing firearms inside the room. The Gestapo also arrested Eva’s brother and father that same day; the four had been betrayed by a traitor in the Dutch underground.

Two days later, they were transported to a transit camp at Westerbork, which is close to the Dutch-German border. After that, they were sent to Birkenau, the biggest Auschwitz death camp in German-occupied Poland, in cattle vans.

“It was terrible for the first hour,” Eva Schloss recalled. “The Nazis were walking around making fun of our humiliation while we had to undress completely naked.” “Welcome to Birkenau,” a Polish kapo, a prisoner of war employed by the Germans to run the camp, greeted them. Is the camp crematorium odorous? There, in what they believed to be shower rooms, your beloved relatives were gassed. Now they are on fire. You won’t see them ever again!

Eva’s arm was tattooed with the number A/5272, which matches the number on her admissions documents, and her hair was shaved. In her memoirs, she recalled, “I climbed into a middle bunk with Mutti [mother] and eight others that first night at Birkenau. Since our arrival, neither food nor water has been provided to us. I slept while lying in Mutti’s arms.

The camp was in terrible shape. They were required to move blocks of stone from one side of the camp to the other and use heavy hammers to chip the stones into little fragments. Eva Schloss remembered that the people in charge of them were “vicious bullies.” They would curse us, threaten us with a rifle, and then beat us up if we ventured to take a little break or did not strike the stones hard enough. They had hunger pangs every day. “There was never more than enough food to sustain us. We developed a food obsession.

Eva was taken from her mother at the start of October 1944. “My nights were extremely miserable now that Mutti was gone, and I found it very difficult to bear the appalling conditions without her comforting arms around me,” she recalled. Eva found it difficult to identify her mother when they were reunited after a month apart:

A pathetic figure with a shaved head sprang to his feet and gaped at me. “Evertje&ZeroWidthSpace” was mouthed by her haggard visage as she took hold of my hand. We were in each other’s arms again after she painfully and slowly descended from the top bunk. She nearly perished from starvation. Her blue eyes had sunk into her skull sockets and her cheekbones were sunken. She gave me a curious glance.

When Eva woke up one morning in January 1945, she discovered that the barracks was silent and peaceful; the SS guards, dogs, and kapos had all disappeared, having escaped before the Allies arrived. On January 27, 1945, Russian forces freed her from Birkenau.

She soon went to the main Auschwitz camp in search of her brother and father. She encountered a middle-aged man who had almost no face left, only a skeleton’s skull, from which pale brown eyes glowed, but she was unable to locate them. In Dutch, she said, “I know you.” He rose up slowly and awkwardly, tall and dignified nonetheless, and bowed slightly to me, saying, “I am Otto Frank,” as she remembered in her memoirs. I take it that you are Eva Geiringer? The tiny Anne’s pal He then embraced me and held me in his arms.

One of Elfriede (“Fritzi”) and Erich Geiringer’s two children, Eva Geiringer was born in Vienna on May 11, 1929.

When the German army invaded Austria in March 1938, the family escaped first to Belgium and subsequently to Holland, where Erich Geiringer could continue to work as a shoe manufacturer.

They moved to the house across from the Franks in Niew Zuid, Amsterdam, at 46 Merwedeplein, where young Eva grew close to Anne Frank.

In a subsequent interview, Schloss said, “We would play hopscotch, skip, or do things on our bicycles, or we’d be gossiping about the other kids—all the things little girls do.” The mother of Anne Frank “would make lemonade… and we would sit drinking together in the kitchen.” Anne and Eva weren’t the same kind: Eva Schloss claimed that Anne was far more refined than she was, and that I was more of a tomboy. She was more of a typical girl, drawn to boyfriends, movie stars, and clothing. They grew up together till the war arrived and everything changed; Eva Frank survived while Anne Frank died in Bergen-Belsen in March 1945.

When Eva and her mother returned to Holland at the end of the war, Fritzi Geiringer encountered Otto Frank, the sole surviving member of the Frank family, whom she would eventually wed.

The Red Cross sent a letter to the Geiringers on August 8, 1945, informing them that Eva’s brother and father had both died in April of that year.

Eva returned to school and graduated from the Amsterdam Lyceum with honors. After that, she started taking pictures, and in 1949 she was hired as an apprentice in an Amsterdam photography studio. However, she was unable to settle in Holland, so in 1951 she sailed to London, where she began working as a freelance photographer after first working at a picture studio in Wolburn Square. She started an antiques company in northwest London in 1972.

Eva Schloss was a founding member of the Anne Frank Trust UK and participated in national events, such as ZeroWidthSpace, to educate the youth against prejudice and hate. She was awarded an honorary degree by the University of Northumbria in 2001, and at a small ceremony in London in 2021, at the age of 92, she regained her Austrian citizenship. When King Charles visited a pre-Hanukkah reception at the Jewish Community Centre London in Finchley Road in 2022, she danced with him.

Regarding the King at the time, Ms. Schloss, who was 93 at the time, stated: “He was sweet, he really took part, he seemed to enjoy it.”

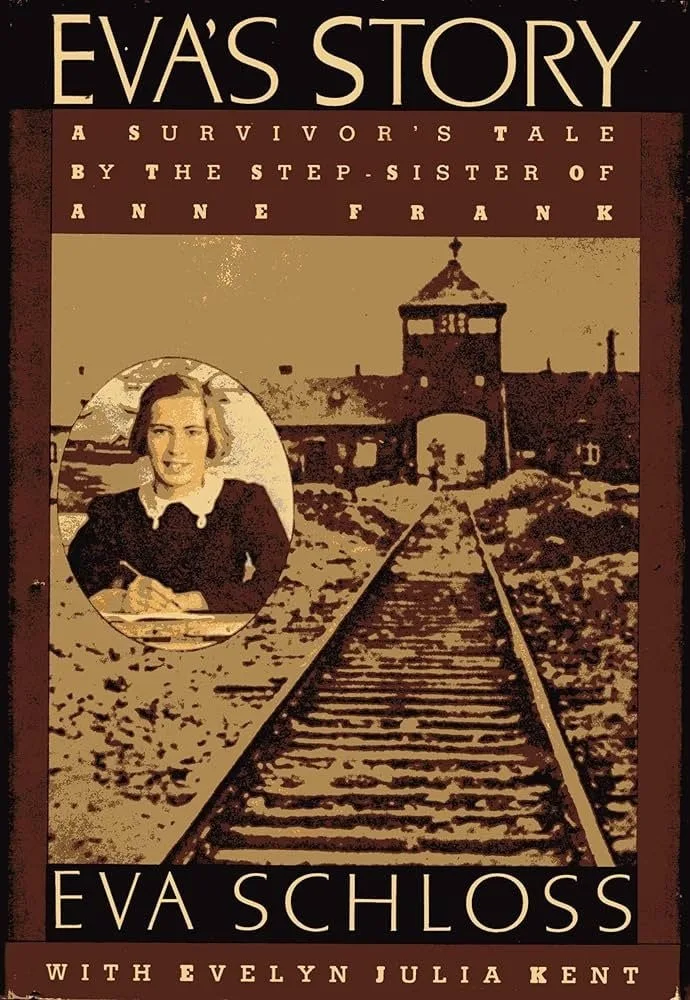

She co-wrote the autobiography Eva’s Story with Evelyn Julia Kent in 1992. She also co-wrote the children’s book The Promise: The Moving Story of a Family in the Holocaust with Barbara Powers in 2006 and After Auschwitz in 2013.

She wed Zvi Schloss, an Israeli economics student, in 1951; he died before her, and she is left with their three daughters.